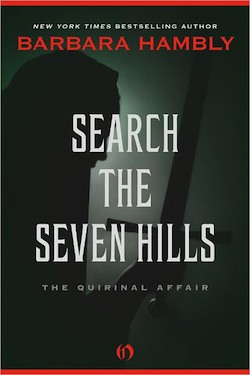

(Originally published from St. Martin’s Press as The Quirinal Hill Affair.)

1983 was, it appears, a busy year for Barbara Hambly. Joining the second and third volume of the Darwath trilogy, The Quirinal Hill Affair (retitled Search the Seven Hills for a brief reissue in 1987) appeared on the shelves of discerning bookshops.

And shortly thereafter, as far as I can tell, seems to have disappeared.

A shame, because The Quirinal Hill Affair/Search the Seven Hills is a truly excellent story. It’s possible that I hold this opinion because Search the Seven Hills is a book which could have been especially designed to push all my geek buttons—but I don’t think that’s the only reason.

Search the Seven Hills isn’t a fantasy, but rather a historical mystery set in Trajan’s Rome. It’s the story of the philosopher Marcus, a young man of the senatorial class, and his drive to find out what’s happened to the the girl he loves after she’s abducted from the street in front of her father’s house.

Tullia Varria is betrothed to another man, but Marcus cares for her desperately, despite all the consolations of his philosophy. His search for her leads him into places extremely unsuitable for a philosopher of his class, and his growth as a result—as a man and as a philosopher—is one of the most interesting things about the book.

Search the Seven Hills is also a story about Christians, for Christians—who, according to the common wisdom of Rome in the second century CE, eat babies, despoil virgins, and commit the most outrageous sacrileges—are implicated in Tullia’s abduction. Hambly sketches with great skill the precarious position of a cult seen by the powerful as a religion of slaves, foreigners, and madmen. She doesn’t neglect to show the incredible and contentious diversity of opinion within the early Christian community in Rome, either—if there’s one thing every Roman, and not a few early Christian, authors agree on, it’s that Christians argued as if the world depended on it. And Hambly’s Christians don’t stop arguing even in the cells of the praetorian guard:

“Your priest?” rasped a man’s voice, harsh and angry. “And what, pray, would he know about it, or you either, you ignorant bitch? The whole point of Christ’s descent to this world was that he take on the appearance and substance of humanity. ‘For the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us…'”

“Now, wait a minute,” chided another man. “You say, ‘appearance,’ but our priest has assured us that the entire meaning of the sacrifice of Calvary was that Christ take on the true nature of a human being. That he was, in fact, a man and not a god, at the time he died.”

“Your priest is a fool!” screamed a shriller voice. “Who consecrated him, anyway?”

As someone who spent many a long college hour being quite baffled by the vehemence and frequency with which Donatists and Monophysites and Arrians and Docetists denounced each other as impious idiots, Hambly’s Christians—both in their squabbles and in their loose-knit communal cohesion—strike me as delightfully plausible. And not only the Christians, but her grip of the details of Rome in the second century, not just telling details of city life, but things like the ethos of the senatorial class, the relationship between wealth and status, marriage and the Roman family, makes the setting immediately believable.

The characters, too, are real and believable. Particularly Marcus Silanus, in whose strained relationship with his father and family we see some of the less pleasant faces of Roman family life, and from whose point of view the story is told; the Praetorian centurion Arrius, who combines a certain brutal pragmatism with shrewd understanding; C. Sixtus Julianus, “an aristocrat of the most ancient traditions of a long-vanished republic, clean as a bleached bone, his plain tunic the colour of raw wool and his short-clipped hair and beard fine as silk and whiter than sunlit snow,” a former governor of Antioch with many secrets and keen powers of deduction; and the slaves of his household. Even minor characters are solidly drawn.

The search for Tullia Varria and her abductors is a tense one, with many reversals and red herrings both for Marcus and for the reader. Enemies turn out to be allies and allies turn out to be enemies: the climax involves a night-time assault on a senatorial villa and a confrontation in a private lion pit. And—although the Classics geek in me cries out for more Roman stories like this one—I have to say that it’s a very rewarding finish to an interesting, twisty mystery.

Liz Bourke is reading for a postgraduate degree in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin.